When Care Isn’t Enough: Administrative Burden in Federal Higher Education Pandemic Emergency Aid Implementation (2022)

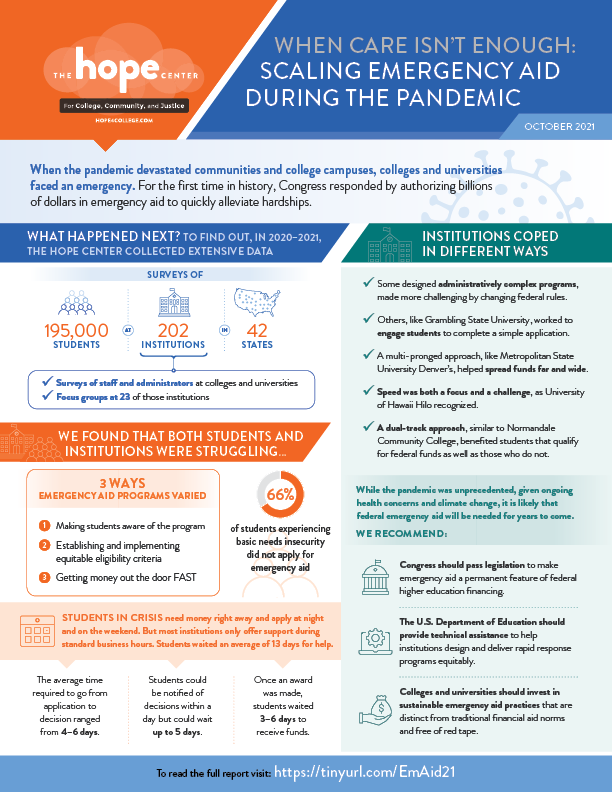

Departing from traditional financial aid policies, during the pandemic the federal government

introduced emergency aid to higher education for the first time. This study examines the implementation

of that program, including students’ need for and access to the resources and the processes they navigated

to obtain help. We identify multiple forms of administrative burden present, and using both survey data

and focus groups, explain how they affected students and institutions. The psychological costs of

administrative burden were particularly substantial and should be addressed in future programming.